Copyright © 2025

Stacy's Music Row Report All Rights Reserved

Stacy's Book Reviews

(Author of Comedians of Country Music, The Carter Family: Country Music's First Family, Classic Country and The Best of Country: The Official CD Guide and contributor to Country Music Stars and the Supernatural and The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History& Culture and Kosher Country: Success and Survival on Nashville's Music Row)

Classic

Country by STACY

HARRIS (January

1, 2000)

Kosher Country: Success and Survival on Nashville's Music Row by STACY HARRIS (1999)

The Best of Country: The Essential CD Guide by STACY HARRIS (1993)

If a review peaks your curiosity, please consider making a purchase through its Amazon cover art link (thumbnails above and below). Commissions I earn through your purchases make updates possible.

You've

heard at least one version of the likely apocryphal amazement of a

Wings fan exclaiming "You mean Paul McCartney had a band before Wings?"

Sir Paul, tackles any honest incredulity head on, in this book's Foreword; an introduction to the oral history of Wings that begins with McCartney's reaction to the resurrection of the rumor of his demise as it spread world-wide in the autumn of 1969.

His point, as he ponders it more than a half-century later, is that the Beatles' breakup left him dead ''in so many ways... that were sapping my energy, in need of a complete life makeover.''

In

retrospect, McCartney found that sense of "isolation'' was ''just what

[he] needed" in order to "shape my artistic life for the rest of my

career, including a wide range of Wings songs I still play in my

current set."

McCartney credits this book's co-author/editor Ted Widmer with the ability ''to

take these Wings stories that, to me, are just my memories and research

them and go more deeply into them than I ever could...lovely details,

many of which I hadn't thought of in over fifty years.''

Recalling the joy of his second career, McCartney marvels a period in which ''we didn't have to explain ourselves. That was one of the greatest things.

"I

do remember that when [McCartney's wife] Linda joined Wings eyebrows

were raised, and not only in the press, Mick Jagger adding 'What's he

doing, getting his old lady in the band?' But in the end no one

can deny that it worked out great..."

The proof is in these

photo-filled 576 pages (over 500,000 words, but who’s counting?) documenting

Wings’ history through the words of band members, Lennon and McCartney scions, the

proverbial many others including Chet Atkins with whom Paul and Linda McCartney

spend quality time in Nashville. (Who

knew that, during the course of one of their conversation, Atkins gifted

McCartney a copy of Peter Tompkins’ Secrets of the Great Pyramid?)

The multi-chaptered book

closes with band biographies, detailed Wings discographies, a gigography, an annotated

timeline, acknowledgments and, of course, an index; all of which will please

serious readers.

Once upon a time- during the Stone Age and well before the advent of

media training and press kits, the content of which assumes journalists do

not do their homework and need publicists' equivalent of CliffsNotes

in order to conduct an interview- interviewees were capable of uttering

a spontaneous thought. A moment of candor- be it vulnerability or

outspokenness- did not come with a price.

During

more recent times, amid the supposed security of unctuous interchange,

social media has amplified the fear that someone- a company head

honcho, name brand or spokesperson, an entertainer, publicist or

manager, even a candidate or elected official- is going to say or do

the (perhaps unforgivingly) "wrong thing."

Is there anyone who can sweep up? Enter the crisis manager.

Absent a magic wand, but

assisted with advice from “public relations, marketing, branding and other

experts,” Edward Segal not only has a grasp of a crisis (defined as “anything that can

damage the credibility, image, reputation, bottom line, activities or futures

of brands or companies, affect the morale of employees, make it harder to

recruit or retain workers, or create a risk of litigation”), he knows what

needs to be done to prevent, contain or ameliorate crises among

individuals (prominent or otherwise), agencies, corporations et al.

With an alphabetical

approach, “nearly A” (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences) “to Z” (Jeff

Zucker), Segal visits crises familiar and otherwise, tackled and avoided in a

manner that informs without beating the reader over the head in general, nor condescension, in particular.

Pointers for the Supreme

Court? Segal suggests them. He also examines actor Will Smith’s famously

“apologizing for creating a crisis.'

The author’s Taylor

Swift chapter subtitled “When You See Something. Say Something” is ultimately a

mixed review, given the observation of one of Segal’s experts, a PR firm’s

senior media consultant, that, as a chapter subheading notes, “Speed Matters.”

Swift is

highlighted on the book’s cover, but The Crisis Casebook... also contains a

chapter devoted to Dolly Parton.

Segal cites several of

Parton’s philanthropic endeavors and the obstacles that have come with them,

including Dolly’s Imagination Library.

Missing, due to post-publication timing of Segal’s book, is notice that the

Imagination Library is no longer serving 18,000 Clark County (Las Vegas),

Nevada children under five, due to a lack of funding by the state legislature.

While that “bad look” comes too late for Segal’s analysis, it’s surprising that any ink about Dolly Parton in a handbook on crisis management would fail to include Parton’s most famous business-related faux pas: remarks in the January, 1994 issue of Vogue castigating Jews in Hollywood that circulated worldwide and resulted in Dolly’s apologizing to the Anti-Defamation League.

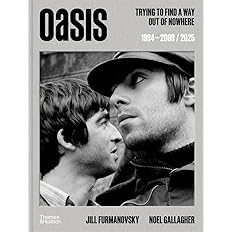

Oasis:

Trying to Find A Way Out of Nowhere... is a voluminous coffee-table book

featuring the work of award-winning photographer Jill Furmanovsky.

Furmanovsky,

who took full photographic advantage of her unlimited access to the group, first

met the English rock band in December, 1994.

Affecting a low-key presence for which she was rewarded when working “with

Oasis intensively from 1995 to 1997 at the height of their fame,” Furmanovsky was soon a welcome contiguity,

unobtrusively “shooting on tour or in a recording studio,” when not otherwise

found at soundchecks, hanging out in dressing rooms and photographing Oasis’

concerts while on the road.

Oasis’

lead guitarist and vocalist Noel Gallagher contributed the foreword to this photographic retrospective, noting the group’s 30-year-association with

the photog whose photography captures “love for the art itself, and with respect

for the artist, and all that comes through in the photos.

Even

though

this collection of beautiful photographs, film strips and contact

sheets represents “only a fraction of the photos I took of the band,”

it is an historical, photographic record of what Oasis fans would have

captured

had they been that same “fly on the wall” with Jill Furmanovsky’s

photographic

skills.

Oasis

founder and lead vocalist Liam Gallagher was already working with three other

founding members in 1991 when Liam asked his older brother, Noel to join what

became a quintet only when Noel’s conditions were met: He would become the band’s de facto leader

and exclusive songwriter.

Four

studio albums later tensions were already such that the Gallagher brothers were

clashing. The fallout led to the

departures of other band members, other musicians joining the group and an

eventual “hiatus.” Simon Spence, Johnny

Hopkins and Laura Barton contribute their expansive thoughts on Oasis’ early,

mid and late eras.

In the

end, the music prevailed and in 2024, after Liam and Noel had established

themselves as successful solo artists, the brothers regrouped with founding

members Paul “Bonehead” Arthurs and Paul “Guigsy” McGuigan, as well as former

Oasis bassist Andy Bell. The result is

that in 2025 a new generation of Oasis fans are able to relive their parents’

and grandparents’ excitement, not only through Jill Furmanovsky’s more than 500

largely previously unpublished archival photos, but perhaps at one of the stops on

Oasis’ 2025 reunion tour; a career achievement that dovetails nicely with the

availability of Furmanovsky’s latest book.

I

was first introduced to Randy Travis when I accepted a media invitation

to attend a "Top Ten" party in celebration of Warner Bros. Records'

newly-signed singer's debut single. I'd been a guest at scores of

"Number One" parties but with country music in a slump I guess someone

felt a redefinition of chart success was in order.

There needn't have been any worry. By the day of the soirée

the lightening-speed of Travis' career trajectory was such that one of

his handlers made a very public gesture of taking a finger to the "10"

portion of the iced

inscription on the frosted celebratory cake and xing out the zero

signifying what had fast and officially become a Number One party.

That Randy Travis has sustained fan popularity, if not his rapid-fire

and prolonged chart success, explains why, with several published books

about Travis from which to choose, Diane Diekman saw an untapped

opportunity to enlarge upon and

otherwise update previous biographies, hagiographies and notably Travis’ own “ghosted” 2015 authorized autobiography

(complete with a disclaimer re: its accuracy).

The latter, sans an

index, let alone footnotes or endnotes, was published two years after Randy all

but lost his speaking voice as a result of a stroke suffered two years

earlier. A decade later, Diekman’s

heavily-researched work (complete not only with an index and endnotes, but also a

Randy Travis discography) amazes as it packs so much content into virtually

every page.

The author’s account of

manager Lib Hatcher’s role in, and alleged often Svengali-like control of, Randy

Travis’ public and private life remains even-handed despite the singer’s former

wife’s refusal to be interviewed for Randy

Travis: Storms of Life.

It would have been

informative had the subject of Diane’s biography, through the remarried

singer’s wife and official mouthpiece, Mary, elaborated on the time frame (two

months) between the National Examiner’s

front-page article “Randy Travis Angrily Fights Reports He’s Gay” surfacing

(based entirely on the supposition Randy “wasn’t married because he was a

closet homosexual”) and the Hatcher-Travis 1991 May-December wedding (impulsive nuptials,

apparently a marriage of convenience, occurring as an all-but-confirmed

bachelor’s overreaction to gossip).

Indeed the formerly

long-time live-in couple’s marital bliss was short-lived, straining their

professional relationship as well. That begs the question of why it took nearly

18 years, Lib’s alleged affair and the cooling off of Travis’ career for Randy

to file for divorce. Further, post-divorce,

it took Travis more than two years to fire his ex as manager.

The references to

cellular technology in Diekman’s book also left this reader a little confused. Given

that cell phones were expensive, unreliable and mainly used by businesses from

the 1980s through the mid-1990s, was Randy Travis’ tour bus equipped with a

cell phone, with which Randy communicated with the President George H.W. Bush

White House in 1990? (Readers are informed that, never a fan, as of 2008 Travis

did not own a cell phone.)

If a paperback version

of this book is on the horizon I would suggest its index include Andrew Skaggs. Randy Travis accepted an urgent early morning

request to stand in for the young boy’s father’s scheduled appearance at a CMA

press conference as Ricky Skaggs needed to be at his son’s Roanoke, Virginia

hospital bedside following what was likely a passing trucker’s mental breakdown resulting

in a young passenger being shot in the face as the car driven by his mother, Brenda traveled

Interstate 81.

Referencing the incident

Diane notes that following surgery the seven-year-old was in “stable condition,”

a common but technically incorrect description that might be tweaked in a

paperback. (Hospital patients may be in excellent, good, satisfactory, fair, serious,

critical, guarded, poor or grave condition and/or variants but “stable,” rather

than a defined condition, is merely shorthand for indicating symptoms or vital

signs have stabilized, are within a normal range and/or are not improving nor

deteriorating.)

As indicated, I’ve known

Randy for decades but only after I moved in to my present condo did I learn that

he and Mary lived in the unit next door! Finding

someone with whom you’ve been acquainted has become your next door

neighbor creates a new learning curve, but I can honestly say that I

learned as much or

more about Randy from the perspectives of the others Diane Diekman

interviewed

as I have from my own disparate interactions.

Travis fans who

have ever wished to be that fly on the wall backstage, in the recording studio during one of Randy's session,

on Travis’ bus and/or on tour with Randy back in the day, may consider Randy Travis:

Storms of Life to be the next best thing.

Dedicated

to "every runner, general, bookkeeper, studio manager, assistant

engineer, receptionist, gofer, tape operator, driver, session musician,

maintenance tech and studio rat who made all this happen," Martin

Porter and David Goggin proceed to regale readers with the inside story

of Record Plant Studios. Founded by audio engineer Gary Kellgren on the West Side of Manhattan in 1968,

the world's first living-room-style recording studio, Record Plant

Studios was immediately well on its way to expansion out west (Los Angeles, Sausalito) and the

musical empire it became during the 1970s, courtesy of its

groundbreaking technology and the success of its flagship artist, Jimi

Hendrix. Diana Ross, Frank

Zappa, The Rolling Stones, The Eagles, Patti LaBelle, Todd Rundgren, Laura Nyro, Neil Diamond, The J.

Geils Band, Stevie Wonder, The Fraternity of Man, Billy Joel and other hippie era faves followed, even as the studio's

co-owner, Chris Stone's plans to expand the brand to Nashville and

London fizzled. Stone, who confused actor George Hamilton with

George Harrison at the studio's '68 opening night party, redeemed

himself booking Harrison and George's fellow former Beatle John Lennon

for respective solo sessions. Lennon's "second home," Record Plant typified the sex (Al Kooper likened the studio to "a sex dispensary''),

drugs (drug busts leading to the studio's entry password, "Buzz me in")

and rock 'n' roll. (As The Turtles' Howard Kaylan put it, a rock

star could take a groupie into one of Record Plant's bedrooms "and she

wouldn't emerge for days. ("They

would feed her, drug her, they would pass her around and then several

days later she would emerge, probably the worse for wear. It was

the last of the great decadent studios.") With

session staples such as "a Bayer aspirin

bottle full of coke that was

constantly being replenished [from the album budget]," record label

invoices containing "plenty of padding for parties and payoff,"

underworld influences, changes in the music, the need for technological

updates, and studio partnership dissolution, the ensuing mayhem at The Real Hotel California inevitably came to an abrupt end. But while the rebuilding of Record Plant LA

following a 1978 fire shifted the studio's emphasis from recording to

film and television production, and the 1980s ushered in the decline of

Record Plant NY, Record Plant Sausalito, which also suffered in transition, reopened in 2024 at its original location. Just as the music never dies, its history is preserved and the beat goes on...

In

the closing pages of this book, Nancy Jones (or her ghostwriter, Ken

Abraham, take your pick) writes "Now, regardless of what else you may

have seen or read or heard, that's the cold hard truth about George

Jones and me." That

summary bookends a disclaimer found in the beginning of Playin' Possum...,

namely an "Author's Note" containing this disavowal referencing Nancy's

second (late) husband: "George always said that I would tell you

anything and everything... so I have tried. But I... have relied

on other individuals to help me describe certain details that I didn't

know." Therein lies the rub... Both

Joneses- separately and together- have admitted to having experienced

betrayals of trust, but a trust doesn't have to betrayed in order to be

misplaced. Based

on Nancy's narrative, however, the reader has a gut feeling that Nancy

knows that, her muse found elsewhere; its source a recent "spiritual"

awakening that "has compelled me to share

the rest of our story so that other people living with addiction or

spousal abuse can find hope." Fine

and dandy, though there are a lot more time-tested, proactive and

otherwise effective means to achieve that stated purpose. But I

digress... Before Nancy Ann Ford Sepulveda Jones "got" religion she wrote another book, Nashville Wives: Country Music's Celebrity Wives Reveal the Truth About Their Husbands and Marriages (with ghostwriter Tom Carter).

In so doing, while the spotlight largely and appropriately shone

elsewhere, Nancy didn't entirely exclude her own expertise from the mix

of what most charitably might be termed unchallenged half-truths she

extracted from those interviewed for that book. In the Nashville Wives..

chapter about herself, Nancy wrote "It would be unfair if I didn't apply the

same rules of frankness to myself that I saw from other wives." Is

the other message of this book an admission that Nancy was not to be

fully believed when being interviewed, dishing with Tom Carter and/or

otherwise interviewing

others about her and their experiences before (she got religion)?

The answer is found in the language of the overlapping material in both

books, highly recommended precisely for that reason. Two

(curiously) male ghostwriters (Nancy does not indicate whether she

approached Carter this go-round before contracting with Abraham) apparently failed to ask the question. Both

books would have more impact if either writer had been less

intimidated. While these are Nancy's narratives, memories can be

refreshed and accounted for accordingly if the subject's second pair of

eyes and ears fails to signal when narratives don't ring true.

In lieu of such assistance, Nancy’s approach to “the

truth” is to anticipate skepticism and to answer her perceived critics. To

wit: “Some people might say ‘Oh, Nancy stayed for the money, or she stayed

because it was George Jones, country music star.’ “That’s

nonsense. “There was

no money for the first few years that George and I were together…”

Of

course, no lawyer was going to represent The Possum pro bono and fighting

lawsuits (even copycat and/or nuisance ones among those numbering three digits that George

and Nancy knew would be dismissed) would be impoverishing. In

fairness to Nancy, her publisher's lawyers may have cautioned her

editor,

given the reality of the Jones' past legal history, expressing any

nervousness they might have had about Nancy being more specific in

several accounts that lack detail. As examples, Nancy references

(though not by name) George's "former manager from Roanoke" and an

unnamed attorney (John Lentz? Nashvillian Lentz also briefly served as Jones' personal manager.) Then again, Nancy mentions Jones' attorney Joel Katz by name. She has no problem skewering Ronnie Gilley, treads lightly re: George's Strangely referring to Woody Woodruff

as "one of our employees," Nancy seems dismissive of the prominent

Williamson County legal and political power player in a manner akin to

identifying Pope Francis as a member of the Catholic Church. Nancy expresses admiration for an unnamed male Tennessean

entertainment reporter "with ties to USA Today" whom she knew "fairly

well" but identifies only as the writer (a guest in George's home

during the interview occurring between 1983 and 2013) who asked about

George's grandchildren and, having received a response that was more

than the scribe bargained for, acceded to Nancy's demand "Don't you

print a word of that. I mean it." ("'I promise you, Nancy. I

won't.' ("And he didn't.") And

how does Nancy address the March 6, 1999 single vehicle accident

that nearly killed her husband? Very delicately. No mention

of Ricky Headley,

let alone Jones' casual attire reflecting his certainty of the verdict

when he entered the Williamson County's courtroom from which, having

successfully "lawyered up," he emerged with a slap on the wrist. (Bill Faiman was an honorary pallbearer at Pee Wee Johnson's funeral.) Though Nancy Jones mentions Evelyn Shriver in Playin' Possum...,

she does not embarrass Evelyn by repeating Shriver's famously

astounding defense of the reckless, alcohol-fueled disoriented driving

that nearly killed her client, potentially taking others along with him.

publicist "Big Daddy" (a/k/a Kirt Webster) and mentions an employee by first name only.

Playin' Possum...

arguably occasionally fails to adhere to those boundaries, but whether

graphic descriptions constitute TMI or candor about some things so as

to distract from a lack of candor about others is every reader's call

based on how much they know, how much they think they know, how much

they are in a position to know and how much they want to know.

While not specifically written for, let alone about, women in the music industry, Randi Braun's Something Major: The New Playbook for Women at Work has universal application.

Given

the pronounced workplace inequities faced by the women of Music Row,

with the Row's emphasis on box-checking and often skewed definition of

leadership, Braun's book is particularly welcome and timely.

Record

Row has never been accused of being ahead of the cultural curve. Hence

the rules of the "old playbook" ostensibly resist collective challenge

among its inhabitants.That said, women who embrace Randi (Fishman)

Braun's presentation of a revised and updated approach to how women

present and represent themselves in the workplace would seem to have a

leg up on the upwardly-mobile competition.

Braun's workplace self-help guide, while heavily-sourced, retains a conversational tone. While acknowledging the familiar hot buttons that create obstacles to success (Think inner critic, imposter syndrome, what Bonnie Low-Kramen has termed "toxic femininity" et al), the author provides "real life" relatable examples of what businesswomen encounter, how well they have handled these frustrations and, in some instances, the suggestion of a better approach, such as how to thrive, rather merely survive, courtesy of the "new playbook."

From learning the specifics of "three reasons brilliant women go off the rails" to the "new playbook"'s approach to building boundaries and "owning your message by writing better emails," Braun's handbook's emphasis on the tools of wellbeing ought to be utilized by, if they are not already incorporated into, the counseling services offered by MusiCares and the Music Health Alliance.

Best

known as the focal point of The Anita Kerr Singers, the award-winning

background group, so essential to launching and/or sustaining the

careers of many of the pop and country hit makers of the latter half of

the 20th century, Anita Kerr has never been one to

brag about her accomplishments.

The

Memphis-born (1927) musical prodigy took

her piano lessons to a new level by age 10 when, doubling as a church

organist, Anita wrote arrangements for a female vocal group featuring

14 classmates.

While

singing with her sisters on their radio show (a family tradition begun

by their mother, who hosted a WHBQ radio show), Anita Grill,

as the prodigy was then known, became a WHBQ staff musician. (Anita,

a church and skating rink singer and organist, also worked at WREC Radio.)

At

age 18, having graduated from parochial school the year before, the

budding composer began perfecting her songwriting, moving to Nashville

in 1948.

In

Nashville Anita found work at radio stations WMAK where, as a staff musician,

she formed a five-piece vocal group.

Word

caught on and Anita performed sporadically on Nashville’s WLAC Radio before coming to the

attention of WSM Radio where she worked with

an eight-piece vocal group, enduring the awkwardness of replacing the

popular Alcyone Beasley after WSM’s Jack Stapp fired Beasley.

Decca Records A & R Director Paul Cohen hired radio announcer Al Kerr’s wife (since 1947) away from WSM and it

was Cohen who named the incarnation of the vocal group that had

survived personnel changes, The Anita Kerr Singers.

Anita

began playing sessions in 1949 and through the 1950s she sang

background for singers ranging from Burl Ives to Ernest Tubb, traveling to- and-from recording

studios in New York and an emerging recording center: Nashville.

Honing

the composition aspect of her craft resulted in Dean Martin’s 1953 recording of Anita’s Til I Found You.

While

in Music City Kerr played accordion on the Grand Ole Opry. She

and her now eight-piece vocal group soon became regulars on the Opry’s Prince Albert-sponsored show.

Owen Bradley signed to Anita to

Decca Records in 1951 and, by the time The Anita Kerr Singers won the Arthur Godfrey Talent Scouts competition,

the singers were now a quart.

Anita, Louis Nunley, Dottie Dillard and Gil Wright expanded their

recording repertoire to include jingles when Anita wasn’t writing

arrangements for Roy Orbison, including the strings portions of

Orbison’s biggest hits.

In

1961, Chet Atkins (who Anita first met

backstage at the Grand Ole Opry) hired Anita as an assistant A & R,

signing the quartet to RCA

Victor with terms of a contract that allowed them

to continue to freelance for other labels. This

was only fair if, as alleged, Kerr did most of the work (for scale)

while Atkins, Anita’s session producer largely in name only, would

remain in the studio just long enough to sign the time cards that would

result in a hefty paycheck for Atkins' “contribution” (Kerr was one of AFTRA’s

founders), before leaving the group to essentially produce themselves

while Chet headed out to the golf course.

When

not recording in Nashville with Al Hirt, Brenda Lee, Ray Charles, Jim Reeves, Rosemary Clooney, Brook Benton, Pat Boone, and a host of other artists, The Anita

Kerr Singers recorded their own albums in the countrypolitan style that

was soon dubbed “the Nashville

Sound.”

Moving

from the fiddles and steel guitars that dominated traditional country

songs, a sound that was dying at a time when rock ‘n’ roll was taking

off, Kerr’s transition to the lush sound of stringed instruments,

representing what Chet Atkins liked to call the sound of pocket change,

meant adapting to self-taught studio musicians who, while they couldn’t

read music, were able to read chords changes.

As

the music because more sophisticated, Atkins received the credit,

though he would correct those who failed to mention the roles Anita

Kerr and Owen Bradley played in the development of the Nashville Sound.

One

of the first women to produce country albums, Anita received her first Grammy nomination

in 1963.

Another

Grammy nomination followed in 1964 and, in 1965, the Anita Kerr Singers

bested category competitors (most notably The Beatles), winning the year’s “Best Vocal

Group” honors.

By

the time of a repeat Grammy win in 1966, after 17 years in Nashville

(working as her vocal group’s composer, arranger and leader), at Henry Mancini’s urging, Anita abruptly moved to

California with her two children and second husband, Alex

Grob.

Having

given notice to Dillard, Wright and Nunley, none of whom had any

interest in joining Kerr and family in the cross-country move, the

vocal group disbanded (rebranding, with Priscilla Mitchell rounding out

the quartet).

Anita

was not prepared for the lawsuit that followed when Dottie, Gil and

Louis learned that Kerr would be using the erstwhile quartet’s name

when she debuted on Lawrence Welk’s network TV show.

In

1969 Kerr signed with Dot and, by 1970, after years recording, notably

for RCA and Warner Brothers Records and as

the leader of the Anita Kerr Orchestra (Kerr was

also known to record under pseudonyms), Anita moved to

Europe.

In

1970, heading the latest incarnation of the Anita Kerr Singers, Anita

commuted from London’s recording studios (where she recorded for Philips Records and oversaw the

production of a Royal Philharmonic concept

album) to her home in Switzerland, where Anita and Alex were raising

their then-preteen daughters.

In

1974, Anita contracted with Word Records to

compose, arrange and produce two albums on an annual basis. There were

a total of nine such religious albums between 1975 and 1979.

In

1975, after writing a Hollywood movie score (Limbo) and recording seven albums for Philips,

Kerr returned to Nashville.

There,

Alex produced The Anita Kerr Singers’ final album of the ‘70s: Anita Kerr Performs Wonder’s (A

vinyl salute to Stevie Wonder) and, in July of that year, Anita

accepted an invitation to appear at the Tokyo Song Festival.

Whether

working at Switzerland’s Montreaux Recording

Studio (1975-1979) or commuting from studios in

London, Los Angeles and Nashville during the ‘80s, Anita remained

active as an arranger and songwriter.

In

1992, Anita Kerr received a NARAS

Award for Outstanding Contributions to American Music.

Having

outlived Gil, Dottie and Louis, at 94, Anita is a survivor for all of

the reasons Barry Pugh suggests in a

narrative abundantly in Kerr’s own words, supplemented by the memories

of those with whom Anita has been associated.

With

a forward by Burt Bacharach, this 285-page paperback features

everything from Anita Kerr’s own practical guide to success in her

polymathic disciplines to the story of why she refused to do an album

with Frank Sinatra.

Complete

with a plethora of photos, discographies, lists of awards, compositions

and songs with which Anita was associated (be it a as singer, writer,

producer, arranger or a combination of these contributions), Barry Pugh

offers a detailed labor of love for Anita and her astonishing body of

work.

With

all of this tender loving care, it’s hard to believe anything has been

left out. However, the addition of

an index, should this self-published book be updated, is highly

recommended.

With

forewords by Mick

Foley, John

Gibbons and Suzanne Alexander, the author establishes from the

beginning that where and how readers recognizes the Brooklyn-born,

Italian son of a family with “Mafia” connections- be it from his own

connection to wresting, baseball or country-music- that identification

will serve as an introduction to this polymath’s range of interests and

career changes.

John Thomas Arezzi was

introduced to wrestling as child of ‘60s TV, skeptical of the sport’s

authenticity shortly thereafter, but convinced the “professional”

variety was “fake” when, in 1972, he bought a ticket to a Shea Stadium match.

Far from disillusioned, however, Arezzi became a member of a wrestling fans’ organization and the networking teen found himself bonding with other wrestling fans like Mike Omansky, a future RCA Records exec and grandson of future Family Feud host, Richard Dawson. (Not long after, Arezzi was a house guest in Dawson’s Beverly Hills home.)

Having

made inroads into the worlds of journalism and photography, while

attending a Boston junior college Arezzi was bitten by the music bug

even, as “Mr. Wrestling,” he was hosting early editions of Pro Wrestling Spotlight on

the college radio station. Following

junior college graduation, Arezzi continued his education at Emerson College,

where the sports fan, whose interest extended to baseball, dreamed of

doing play-by-play for the New York Mets as he hosted the

college’s TV station’s sports reports.

Photographing ABC’s Good Morning America host David Hartman’s son, Sean with Johnny Bench almost led to Arezzi’s joining ABC Sports. That missed opportunity led to another stint as a wrestling trade magazine writer and yet another, where- billed as “John Anthony”- Arezzi realized an additional dream by getting into the ring for his first mat match with Dusty Rhodes (i.e. Virgil Riley Runnels, Jr., not to be confused with RCA Records’ artist [Perry Hilburn] “Dusty” Rhodes).

Music

industry followers won’t need to ask why Arezzi left a job with Morris Levy’s Roulette Records, landing a behind-the-scenes job,

during the early 1980s, with the Mets’ organization's North Carolina

farm team.

The

self-described “nutty New Yorker” wasn’t done with the music business,

however. Not when, while still in

North Carolina with the Mets organization, Arezzi befriended- and

booked- a struggling singer who would join him in drinking and doing

drugs: Patty Lovelace.

Returning

to New York where he took a job as an ad salesman, Arezzi moonlighted

as Loveless’ manager (a stage surname he created for the woman with

whom Arezzi was, at that point, in love), planning to record her in the

Big Apple.

The two even made it to Nashville, but the personal and business relationship began to fizzle out at that point which partially explains why “You won’t find John Alexander (or John Arezzi, for that matter) in any biographical information on Patty Loveless.”

Similarly,

the Great American Country (GAC)

cable TV network’s former director of music marketing and the Black River Music Group ex-vice-president

of strategic marketing details professional relationships resulting in

his advancing the careers of Sarah Darling and Kelsea Ballerini, setting the record straight in

the absence of having received the credit due him from an industry best

typified by the ingratitude of others he names including Country Music

Association CEO Sarah Trahern.

From managing to avoid proximity to the WWF sex scandals (reminiscent of the more recent victimization of Olympic gymnasts by their team doctor) at a time when his involvement in the pro wrestling community was his calling card, to, during his Music Row forays, being able to steer clear of the implosions of acquaintances (Mindy McCready, Cyndi Thomson and Jeff Bates), Arezzi regales and informs readers in this 286-page cautionary tale of professional sports and country music.

This is

the story of a tight-knit family fronted by (no pun intended) its

best-known member. (Wayne Warner made his singing debut as a member of Warner Band, playing to an audience at Westfield,

Vermont’s Buzzy’s Barn Dance at the ripe

old age of 6!)

Wayne’s

curious and circuitous road to Nashville began with the odds stacked

against him, when, bullied, he dropped out of high school at the first

opportunity to do so. A regional

favorite with no national/international aspirations, Wayne recorded a

song at a local studio as he was turning 16 that was subsequently

passed around, resulting in Warner being summoned to Nashville to

record an album at Nashville’s Hilltop Studios.

There

Wayne met many of the name session musicians whom he admired and

parlayed the trip into a meeting with famed producer and veteran record

label executive (James) Harold Shedd.

Exiting

the majors, Shedd founded the independent Tyneville

Records label, signing Wayne. However,

the ink on Warner’s contract was hardly dry when routine details about

Wayne’s family came to light, alarming the Tyneville “team.”

It wasn’t

the makeup of Wayne’s birth family (including his sister/manager) that,

in part, torpedoed Warner’s first record label contract. Rather, it was

Wayne’s “modern family,” its legal status, and particularly

composition, being one of personal preference (that, in any other

industry, would likely remain so), that raised questions.

Questions gave way to second thoughts in the form of jitters among the

suits charged with promoting the artist and his recordings.

Clearly,

Wayne’s chosen family came first and and, amid a desire to keep the

peace, an amicable parting between Warner and Tyneville was forged.

Warner's

supportive birth family unit and chosen family intact, the

introverted-but-driven singer/songwriter, used to doing things his way,

at least initially mollified the image-makers and those unwilling to

give the artist creative control. Wayne even lied about his age

when advised to do so, in order to accede to even the silliest of

demands, in gratitude for the opportunities he had been given while

others struggled.

Among

those opportunities was a second chance, when (another) industry mogul Barry

Coburn, the new head of Atlantic/Nashville chose Wayne

as his first signee.

When

Atlantic closed its Nashville office, Wayne took it as a sign that,

independent by nature, his best days were ahead of him as an

independent label artist.

Forming his own B-Venturous record label, Warner blossomed. During the early 21st century Wayne turned out singles, EPs and albums, including a self-titled album, released in 2002, that featured what became Warner’s signature song, Turbo Twang.

Turbo Twang attained

recurrent status when it found new life, four years later, on Wayne’s Turbo Twang’n album. At

a time when Wayne had never heard of the country dance chart, Warner

suddenly learned that Turbo Twang, a club favorite, was dominating it.

With the

success of God Bless The Children (a

philanthropic venture featuring Nashville' All-Star choir), Warner’s fans affirmed

their devotion for an artist who enlisted the participation and support

of a number of the heavy-hitters with whom he has interacted, since the

early days of a “cold call” to one he did not know: Charley

Pride.

Prior to

that time, one of the biggest names crossing Warner’s path was another

singer/songwriter; a 15-year-old Nashville area transplant Wayne came

to know, during the course of their brief musical collaboration, as Taylor Swift.

By 2010 Wayne’s name recognition accorded him an opportunity to record Something Going On with Bonnie Tyler.

At age

58, Wayne reflects back on his career (so far) with a lot of great

stories about names you will recognize. (Warner also includes

some blind items, but either provides some strong hints that will

either refresh memories for those who had knowledge of the same people

and/or events or otherwise makes full disclosure easy enough for anyone

who knows how to use a search engine.)

Backstage Nashville... is peppered with wonderful

photos, but the self-published paperback lacks an

index and a proofreader. The

latter would have prevented typos such as the misspelling of Charley

Pride’s name (Page 7), a reference to “Music Square, East” (Page 64), a (Page

69) reference

to the “Country Music Awards” rather than the Country Music Association Awards (so as

not to be confused with the Academy of Country Music Awards) a mention of Kentucky as the Blue Grass State

(Page 57) and a Page 153 malapropism (“except” rather than “accept”).

Think of Backstage Nashville... as

the diary of an entertainer who, if he has not seen and done it all,

could certainly fool you with his documentation of the people and

events who have shaped his career.

It’s also

a "how to" and, at times, "how not to"

succeed in the music business based on either Wayne’s earning a diploma

from the school of hard knocks or the lessons he’s learned from both

those who have paved the way and his contemporaries.

Martine’s

mother, a Family Circle columnist, raised

her son among New York celebrity neighbors ranging from Vivian Vance to Gene Tunney. Layng,

enterprising son that he was, at 13 had a job mowing his neighbor, Benny Goodman’s lawn and generally acting as the

famed clarinetist’s handyman.

Martine

sold magazines and later slippers, of all things, door-to-door during

the summer of 1960, even managing a trip to Quebec City, Canada before

returning to school for his freshman year, joining Denison’s football

and track teams, while becoming a frat boy alongside his future

brother-in-law, Lee Schilling.

In July,

1961, Denison dropout Layng arrived in New York City where he took a

job a TIME

magazine copy boy, commuting via train to his job

from his parents’ then-home in Connecticut.

After

hob-knobbing at TIME,

for a year, with the likes of Calvin Trillin, Layng resigned, heading for a

vagabond’s adventure in Wyoming before resuming his formal education;

this time at New York’s Columbia University.

Obsessed with John Kennedy's presidential news conferences, an enterprising Layng Martine, Jr. parlayed a friendship with a CBS News reporter into a 1962 Oval Office visit.

Not long

after walking past JFK’s casket a year later, Layng caught the

songwriting bug. Martine

wrote his fist song, Swagger,

cut a demo, got a publishing deal and became a successful New

York-based pop songwriter, all in rapid succession.

While serving as the Lee Schilling’s best man at Schilling’s Georgia wedding, Layng met Lee’s sister, Linda.

Linda’s

mother vomited on the way to that wedding,

while the forgotten marriage license had to be delivered to the

officiating minister via a state trooper. Then,

after a three-day honeymoon in Quebec City, Layng’s draft card arrived.

An

unsuccessful stint as a songwriter (save

for an undisclosed Glenn Yarbrough cut Martine

only learned about years later) for a

division of CBS (at a time when Linda was working as a successful New

York fabric designer) ended when Layng secured and, shortly thereafter,

lost a job as a Madison Avenue ad agency copywriter.

Feeling

‘’like I’m wasting my life,’’ and learning that another of his songs

had been recorded by Bo Diddley, after

the births of two of his three sons and yet

another disastrous professional detour as a fast food franchisee, Layng

focused on his muse. That

rededication led him to connect and sign with Ray Stevens.

Relocating

to Nashville with Linda, Layng’s namesake and Layng’s brother, Tucker, Martine

became a beneficiary of lenient (later tightened) bankruptcy

law.

Two years

out from a bankruptcy ethicists would agree a fiscally-responsible

Layng shouldn’t have declared in the first place, the hits started

coming when Billy ‘’Crash’’ Craddock had a

hit with Martine’s Rub It In. (Craddock’s

summer sensation, following the inevitable end of its chart success,

found new life as a memorable jingle, thanks to a TV ad campaign for S.C. Johnson &

Son cleaning products that had an astounding 18

year run!)

Recordings

of Layng’s song by artists ranging from Barry Manilow to The Pointer Sisters followed

before Martine landed what turned out to be Elvis Presley’s posthumous hit, Way Down.

With

professional success came devastating personal

pain that Layng first detailed in a 2009 New York Times Modern Love essay. The

graphic account is revisited in Permission to Fly’s closing chapter and epilogue,

giving the reader a more complete understanding of the book’s subtitle

and choice of cover art.

Additionally,

Martine’s memoir contains a disclaimer that he has changed names of

individuals and locations, in the name of privacy. In

some instances that detracts or otherwise misleads, as in when a

songwriter to whom Martine refers as simply “Lou” is obviously Lou Stallman. Indeed,

Martine identifies “Lou” as the “writer” of Perry Como's Round and Round and Clyde McPhatter (The Treasure of Love)

when, in truth, the greater good would have been served by properly

identifying Lou Stallman as the cowriter of both songs and crediting

the songs’ other composer, Joe Shapiro.

It is

also worth noting that while, recounting his songwriter’s credits,

including Wiggle Wiggle, Martine

omits mentioning the name of the artist for whom the song was a Top 20

hit (Ronnie Sessions).

Martine’s self-published memoir is also missing an index but, apart from these shortcomings, Layng has produced an entertaining and inspiring read that deserves a permanent place on the bookshelf.

If you've listened to Nobody Makes It Alone (Track #9 from Erica Stone's Antidote) you understand the importance of a support system. You likely also sense that Stone's lyrical message of "pain and hope" was borne of experience.

Stone chronicles, as she channels, the depth of that experience in Gray: A Story of Loss.

In the natural order of things, children outlive their parents. Whenever this particular natural order is disrupted it is incomprehensible.

When it happened to Stone, whose Midwestern sensibilities and idealism took her to Sierra Leone where she became an advocate for orphans and other disadvantaged children caught up in their African homeland’s history of civil war, the pain and inability to justify was magnified.

But

by then, Erica was "all in." Stone's initial human rights

advocacy extended to joining her husband, Jason in opening an orphanage

and adoption agency, though not until Erica, a singer whose dream of a

career in music was about to be realized, was forced to find a Plan B

as her major label record deal fizzled.

The

door that closed opened the door to a dramatic change in direction. Parent

of a son, Justin, Erica became an adoptive mother for the first

time when daughter Jayda (one of Erica's now six living children)

joined the family.

The

3,000-day journey to adoption, involving navigating through the

obstacles of corruption, violence, brutality and deprivation,

underscored Erica’s need for further adoptions, though the

afore-referenced death of Erica’s daughter, Adama was the impetus for

Stone’s determination to make another career change to that of author.

Telling

her story is Erica’s vehicle for communicating the injustices visited

upon refugees and those who seek to rescue them.

The

silver lining for Stone, apart from the therapeutic value of writing it

all down, is that a detour that turned into an opportunity to make the

world a better place has given Erica a larger opportunity to get the

word out about the urgency of ending the collateral damage of war and

dictatorship.

Erica

Stone’s humanitarianism, amid enormous obstacles that have left many

merely cursing the darkness, has not only resulted in her unlikely

platform of published author, a movie based on the book is to follow.

And-

in the meantime, busy mom and new author Erica Stone is making good on

that second chance at her dream of a recording career.

Once

again, with faith and determination, she is beating the odds.

As

her fans know, this is not Lulu Roman’s first autobiography.

Roman

makes up for the latter with some great Hee Haw-related trivia.

Among these revelations is an acknowledgment that, country music

being an acquired interest, at the time she met him Lulu had never

heard of Buck Owens!

Then

there’s that affair Lulu volunteers she had with Don Rich…

It was a harrowing life for little Bertha

Louise (as Lulu was christened) who was placed in an

orphanage at age four, courtesy of her maternal grandmother, and Lulu’s

having reason to believe that her paternal grandfather was actually her

biological father.

Lulu credits her

discovery of religion with turning her life around and for Roman's

success performing gospel music.

For

her part, Lulu returns the sentiments toward Travis, Skaggs and Morgan

and is equally generous in her praise of a score of others, most of

whose names readers will recognize.

There’s a stunning amount of life experience packed into these 160 pages and Scot England does a great job of letting his subject tell her story the way she now indicates it should have been told in the first place.

"Johnny Lee's attempt

at an autobiography is to be commended for its few-if-any-holds-barred

candor, straightforward style and insight."

So reads

the opening paragraph of my review of Lookin’ For Love,

Lee’s first book; a critique published in the December 1990 issue of Country Song Roundup

(Page 20).

My

review of the 1989 book, ghostwritten by Randy Wyles,

cited a number of factual errors. I also pointed out that “the

photo gallery,” supplementing the text, depicted “Johnny with his arm

around celebrities” whose link to/relationship with Lee seemed

“tenuous,” given the fact that were not “otherwise mentioned in the

book.”

As

I read all but the closing page of Still Lookin’ For Love,

I wondered why Johnny had not referenced, to that point, his earlier

book. With the same candor evident in that earlier book, Lee not

only finally got around to mentioning that this is not his first

autobiography, but also to explain that he was unhappy with that first

venture. Further, Johnny allowed Scot England, in Scot’s own words, to

amplify how England and Lee got together, using Lookin' For Love,

and reaction to it, as a springboard for much new material chiefly

about Johnny’s life during the nearly three decades since the

publication of the book titled after Lee’s signature song.

Still Lookin’ For Love is

conversational and anecdotal with a “can’t put it down” quality to

boot! Moe Bandy and Mickey Gilley are

among those who have contributed their observations to Still Lookin’ For Love,

but it is Johnny Lee’s own breezy style that keeps readers

engrossed.

Expect

the unexpected, such as how it came to be that Johnny shook astronaut Alan Shepard’s

foot. Readers will also learn of Lee’s friendship with Ellison Onizuka,

one of the astronauts who died aboard the space shuttle, Challenger, his

bout with colon cancer and why Johnny wears a black rubber

bracelet.

Johnny

Lee’s story is one of overcoming obstacles that began with the

circumstances of his birth. Prone to repeating rather than

necessarily learning from the mistakes of others, Johnny largely owns

his self-destructive tendencies, though he is not above blaming others

when the evidence points toward the proverbial shoe fitting.

Love,

some of it elusive, and repeated loss also loom large in Lee’s life,

but he approaches joy and challenge with a sense of

humor. Those who have the papers on Johnny Lee will be

hard-pressed to suggest anything that Lee has left out of these pages,

be it about Charlene Tilton,

Gilley, Sherwood Cryer or

even someone as tangential as Luke Bryan.

Lee

may never master the art of money management (England Media holds

the copyright to the self-published Still Lookin’ For Love),

but he is self-aware (although arguably selling himself short) to the

extent that, for example, he opines that, were Lee not also a

celebrity, arm candy like Tilton would have been totally out of his

league.

It

is that endearing quality that will enable easily offended readers to

overlook any offense they may take to a section of the book titled

“Adults Only.” Much of the content is no more bawdy nor off-color

than other parts of this book that also may cause some readers to

conclude the always descriptive Johnny Lee, on occasion, provides that

which may be diplomatically described as too much information.

Still Lookin’ For Love,

with a quality, embossed cover, easy on the eyes layout, and plentiful

photo section, suggesting no expense was spared, is a “must have”

book for Johnny Lee fans. It will not disappoint anyone who is

remotely interested in a well-written celebrity autobiography that,

unlike many if not most such endeavors, delivers on its promises.

Titled

after The Nashville Network (TNN) travel show series, hosted by the husband and

wife team of Jim Ed Brown and Becky Perry Brown, in these 232 pages the latter

summarizes her life, before, after and during 54 years spent with “Jim

Ed Brown, Grand Ole Opry Legend and member of Country

Music Hall of Fame.”

After

six months of dating, and much conversation about shared values, Jim Ed

and Becky married.

Among

those shared values were a Christian faith and close family. The

latter did not bode well for Becky, whose relationship with J.E.’s

brazen, outspoken sister Maxine, always rocky, became rockier still

once Becky and Jim Ed became the parents of impressionable offspring,

namely James Edward “Buster” Brown, Jr. and Kimberly Summer Brown.

J.E.'s wife couldn't predict it, but, in time, Maxine’s influence

on Buster and Kim would become the least of Becky’s problems.

While

Becky writes of having lived a near “perfect” childhood and

adolescence, adulthood came with its own set of responsibilities for

the wife of a country star who, while at times content to be nothing

more, often needed the creative challenge she found,

when not raising children, through painting, bowling

and playing tennis.

A

dance teacher and choreographer (Tom T. Hall credits Becky with

teaching him to dance in his Mr. Bojangles music

video), Becky performed on the Grand Ole Opry as one of Ben Smathers’ square dancers.

A

model and makeup artist for the Jo Coulter Modeling Agency, Becky was hired to

administer Ringo Starr’s makeup when Nashville hosted the March 3, 1973 Grammy Awards.

But,

again, life wasn’t always fun. It

often called upon Becky to find an inner strength. That

was certainly the case when she battled breast cancer, for the most

part a private matter, in contrast to the public humiliation Becky

encountered during the fight to save her marriage after learning of Jim

Ed’s affair with his duet partner, Helen Cornelius.

Becky’s ghostwriter, Roxanne Atwood, writes unobtrusively, preserving her subject’s voice.

As Jim Ed’s former publicist, who was in talks with J.E. to ghostwrite the autobiography that ultimately he never wrote (J.E. didn't want to upstage Maxine, whose jaw-dropping memoir was then in the works), I am pleased that Becky included some of the things I had in mind when I pitched the book, intrigued with the uniqueness of Jim Ed Brown’s three careers. These include Becky’s many interests and activities, sprinkled throughout these pages, such as the Eatin’ Meetin’s for which J.E. and Becky have never received the recognition they deserve, even as these potluck dinners among entertainers who would compare unedited notes and let their hair down were the precursors of the commercialized and edited Country’s Family Reunion multimedia series.

As

the author of several books, one of which I thought was unfairly

reviewed suggesting I did not know the correct spelling of Eddy Arnold’s name, after my review of the galleys

did not catch a reference to “Eddie” among several correct spellings of

Arnold’s first name, I’m tempted to overlook the same mistake as it

relates to a photo caption in this, a self-published book listing

Roxanne Atwood as its editor and one of Becky’s granddaughters as its

copy editor.

Much

can happen between the time a manuscript is delivered and when a book

is published (e.g., the erstwhile Williamson County animal shelter Animaland is listed as Animal

Land). And I’d love to know what

led to the errors in the location of Dixie and Tom T. Hall’s first home

and the confusing of Tom’s hometown with that of Skeeter Davis.

Recalling

that Becky and Jim Ed’s daughter has performed as singer, I thought my

curiosity re: her stage name might be rewarded somewhere in the text. A

1990 captioned publicity photo of Kim Ed Brown is included, sans any

explanation.

So writes the author, Freddy

Fender’s daughter, in beginning the preface to Tammy Lorraine

Huerta Fender’s book; Tammy's effort to finish Freddy’s project.

Tammy vainly tried to assist

her father in writing his autobiography; one he gave the working

title From My Eyes,

so Tammy's continuation of her father's work completes Freddy’s

expressed intention to “write a real book [about] … cocaine… heroine,

the penitentiary, divorcing my wife, and why and all

of that.”

Not that all of Freddy Fender’s

days and nights (certainly not during the six decades of a 69-year-long

life he spent entertaining) were wasted, by any means. Yet

Fender dreamed of a book that struck a balance between what Freddy

valued and what he threw away- as well as a movie based on that

book, full of “things written that were significant in my life.”

As Tammy explains in the preface to these 493 pages chronicling the transformation of Texas-born Baldemar “Balde” Huerta and the rise of Freddy Fender, this paperback is but the first volume “of a two-part biography. It covers his music career until 1979… The sequel covers “‘the fall’ and ‘the redemption’ of Freddy Fender.'"

A Huerta family tree and pictorial provides the perfect prologue to a book that fulfills its purpose of detailing the story of the Mexican American El Bee-Bop Kid as native Texan Balde Huerta was first professionally known before eventually becoming "the first established Chicano singer to record rock 'n' roll." (Freddy was in his 20s when his recording of Wasted Days and Wasted Nights was first released.)

A U.S. Marine at age 16, the high-school dropout knew the hardship of childhood poverty. Balde, who grew up in his migrant laborer family's one-room shack, wasn't doing it for sport, but rather out of real hunger, on those occasions when he would dumpster dive.

Always engaging and optimistic, Balde could be disruptive. Debunking speculation, Tammy tells the real story of how her father obtained the scar on his cheek.

In fact, Freddy was not beyond

sabotaging his burgeoning recording career due to his recklessness.

After taking on the responsibilities of

marriage and fatherhood the recording artist (also professionally

known, however briefly, as Eddie Medina, Scott Wayne and for his work

with a pre-Texas Tornados group called Satan

and Disciples- and variations) sabotaged his first taste of

stardom, and faced additional charges, after jumping bail following

Huerta's being arrested in Baton Rouge on a "marijuana possession"

charge.

Fender put his time in custody to good use when he earned his GED and received his high school diploma while in jail. But Freddy's imprisonment came just as Balde was getting to know the first of his three children, his namesake and while Fender's wife was pregnant with Tammy. Remarkably, Tammy was born during her father's time in the penitentiary and he met her for the first time when Louisiana Governor (and famed singer/songwriter) Jimmy Davis got Freddy out of prison in 1963, after Huerta had served three years of a five year sentence.

Like Freddy, Huey Meaux, Freddy's record producer and manager, also served time, though Tammy doesn't fully disclose the much-publicized circumstances, and she is similarly reticent, due to the nature of the crimes, to discuss Freddy's spousal abuse, which, Tammy introduces in the context of how her mother, Evangelina's reluctance to prosecute kept Freddy from more time in the slammer.

No doubt Fender, who first wanted to be known as Flash (in tribute to a favorite comic strip superhero), had a temper. The man who took his stage surname when he glanced at an amplifier, had a jealous streak that was activated whenever his wife or daughter's attention, however innocent, was on another man. Such was the case when Ever and Tammy were watching Tom Jones on television. Hardly approving of Jones' gyrations, Freddy grabbed the TV and threw it out the door!

Apparently, Huerta left much autobiographical material upon which to draw and Tammy exercises a great technique where those first-person accounts survive. She inserts those snippets, quoting them verbatim, in various places throughout this volume, under the title of the book as Freddy imagined it, so that there can be no doubt that, where possible, every bit of this book is from "the horse's mouth."

Fans and members of the country-music industry will be as pleased as her father would have been, to see that Tammy, with Freddy's intention, credits both Jim Halsey and the late Jim Foglesong for their respective boosts to Fender's career.

Tammy writes that Foglesong privately expressed doubts about Huey Meaux, and, though it will be interesting to see what more Tammy writes about Meaux in Volume 2 of her biography, she reveals in this book that Meaux's stunned her with the observation that Freddy did not serve time, as she had been led to believe, for having broken the marijuana laws, but rather because he had been "set up."

Tammy's turn as storyteller also includes the interesting tidbit that Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards issued a pardon on Fender's behalf that Freddy might perform in Australia and in New Zealand (which would not otherwise honor his passport) and yet, the gesture was not enough to gain Freddy entry to New Zealand!

While Tammy clearly admired her father, she captures his gossipy side, such as Fender's references to Tanya Tucker as "a cute brat" and to The Oak Ridge Boys as being "like giggly kids."

As thorough as this book is, there are some factual errors. Among them: Tammy writes that Tammy was named after a TV show of the same name. But, based on the date of Tammy's birth, September 6, 1961, it was likely she was named after after the Debbie Reynolds movie character.

Larry Gatlin writes in the foreword to The Man in Songs… that, upon being asked for his contribution to the project, Gatlin’s unspoken reaction was to ask why “the world really needs… yet another book on Johnny Cash.”

Wit

A Johnny Cash historian and collaborator, Alexander has familiarized himself with the work of several other Cash biographers and discographers (with at least a couple of notable exceptions, Peggy Knight and Stacy Harris), duly crediting them, in the course of adding his own insights and opinions to mix.

The result is an impressive oversize paperback/coffee table remembrance of Cash through the often semiautobiographical lenses of the lyrics, some classic, others obscure, the Man in Black chose to record. John's is clearly a labor of love and a great resource for future Cash biographers, who will seemingly have the convenience of a lot of prior research all in one place.

Familiar photos- several of Johnny Cash's album covers- adorn these pages. Cash fans will be pleased to see these again, but they will likely be disappointed that no ground is broken of the (previously) unpublished photos- of which there are so many I even have taken them- variety.

Remarkably, John

Alexander writes for Cash scholars, Cash fans, country-music fans and

evidently millennials who may know nothing more than the name Johnny

Cash, if that, given that Alexander introduces Johnny Cash Show guest star Tex Ritter (one of the Country

Music Hall of Fame's singing cowboy movie stars who otherwise

needs no introduction) to the latter as John Ritter's father and Jason Ritter's grandfather.

As any author knows, the more photos there are supplementing a manuscript, the higher production cost of the book. University presses have smaller budgets than the biggest-name book publishers and, as I suspect Alexander's publisher is no exception. That being the case, The University of Arkansas Press had to weigh its expenses in light of its more limited (than the major publishers' ) publicity and distribution budgets, deciding as it did where to splurge on, and where to reduce expenses for, Alexander's book.

Alexander's Cash research, to the extent that he includes specific citations, is largely unassailable. But, in some instances, the author's sources are unclear and the reader is left to wonder why, in those instances where he fails to disclose that he is speculating, John professes knowledge of conversations, events, and motives to which he was clearly not privy.

Alexander is on firmest ground when he writes about Johnny Cash. When John writes about Marshall Grant, and briefly of Grant's well-publicized 1980 lawsuit against Cash, charging J.R. with wrongful dismissal and embezzlement of retirement funds, Alexander notes that the parties reached an out-of-court settlement and reconciled. He doesn't cite court records nor other sources referencing the serious embezzlement accusation and its accuracy or lack of justification.

Similarly, though John writes of the rise and fall of Glen Sherley without whitewashing what transpired, he is less candid about the circumstances and secrecy surrounding Hillman Hall's demise.

There are also the occasional typos found here, such as the repeated misspelling of Dixie Deen as well as that of the aforementioned Sherley (the latter as Glen's surname appears in the book's index).

Except perhaps for those he wrote himself (ghostwriters don't always get it right), every Johnny Cash book that's ever been written could be better, though the reasons differ in each case.

But when an author is able to compile and write a Johnny Cash book that all but replaces some of the earlier efforts, that's no small accomplishment. If I wore a hat, I would doff it to John Alexander.

Copyrighted in 2013 with limited distribution, this semi-autobiographical memoir has been updated for distribution now to a wider audience in tandem with the rerelease (also to wider distribution) of a Billy Burnette's CD, recorded last year, of the same name. (Look for my CD review here).

Memphis-born William Dorsey Burnette III writes that the motivation for writing his first book was, and remains, a desire to "set the record straight" about his father's and uncle's place in rock music history. Simultaneously, Billy, who grew up in Los Angeles, shares his own storied musical journey, in the words of the book's subtitle "From Memphis and The Rock 'n' Roll Trio to Fleetwood Mac."

It's a tall order, in a sense, as bridging a musical gap of over one-half century can only be a lesson for readers who are too young to remember the Trio whose members were Billy's uncle, Johnny Burnette, his dad, Dorsey Burnette and the less-remembered electric guitarist Paul Burlison; this, despite the fact that it was Dorsey's leaving that broke up what was, at one point, also variously known as The Johnny Burnette Trio or Johnny Burnette and The Rock 'n Roll Trio.

Then again, fans of The Fleetwoods may not be as knowledgeable about the musical history and cultural significance of Fleetwood Mac...

Some of us remember when Johnny and Dorsey had success pursuing solo careers. And when Johnny's son, Rocky Burnette (Billy's younger cousin- by one month) had a Top Ten hit with Tired of Towin' the Line, the publicity machine went to town explaining the derivation of the Burnette scions' fathers' genre: rockabilly. There are different apocryphal accounts, but the ones that stick include Billy Burnette's. (Billy explains that when he and his cousin Jonathan were toddlers, the cousins' dads, Dorsey and Johnny, wrote a song, inspired by the near fusion of their sons' nicknames, called "Rockbilly Boogie.")

By the time of Johnny Burnette's untimely death on August 14, 1964, less than five months after Johnny's 30th birthday, Burnette had come into his own with hits like Dreamin', Little Boy Sad, and his highest charting hit, (yes, even before Ringo Starr's version) You're Sixteen.

Given more time to flourish, Dorsey Burnette, the older of the Burnette brothers, had written hundreds of songs, 391 of which are included in the BMI database. Some of those songs (Believe What You Say, It's Late, Waitin' In School) were hits for Ricky Nelson and, when Nelson passed on the song, Dorsey recorded his biggest hit as a solo artist, (There Was A) Tall Oak Tree, following it up with the distinctive classic, Hey, Little One.

At one point Dorsey Burnette wrote and produced a Stevie Wonder recording (and, Dorsey's son writes, co-wrote Dang Me with Roger Miller, though Dorsey never received co-writer's credit) before transitioning to what had become a promising career as a country artist, derailed by Dorsey's early death on August 19, 1979 at age 46.

Billy Burnette (who, like his father, was known as Dorsey- until Billy sought refuge in the nickname suggested by his middle name after too many taunts addressing him as "Dorothy") cut his first record in 1960 at age seven, courtesy of the then 20-year-old Ricky Nelson with whom Billy shared a May 8th birthday. At age 11, Billy Burnette cut a Herb Alpert-produced record and, the following year, Billy toured with Brenda Lee.

Pretty heady stuff, considering that Billy didn't play guitar until he was a teenager. The self-taught guitarist and singer/songwriter, the oldest of Dorsey Burnette's seven children, finished high school positioned to accept the first of several offers from producers and record labels, after, at age 16, having turned down an offer from Warner Brothers Records to record Windy (The song went on to become a #1 hit for The Association.)

Thanks, in part, to introductions from his father, Billy Burnette worked with a dazzling array of greats, eventually putting him in the enviable position of being able to amicably cancel the solo record deal he had received, that he might seize the moment and accept an invitation to join Fleetwood Mac. Burnette writes candidly about the group's historic internecine squabbling; dissension that did not end with either Billy's joining or his leaving the band.

In the series of vignettes that make up this book, Billy writes with equal candor about his big Catholic family whose members' behavior is all the proof the Vatican needs to justify the necessity of Confession. Dorsey and Johnny were rough guys who took red devils and beat up record promoters who didn't promote their records. Then there was the time Johnny confronted Hank Snow with a profanity-laced insult...

Billy's own escapades range from a run-in with Charles Manson to a missed opportunity to co-star with Rob Lowe in an Eddie Cochran biopic. (The movie was never made, but the idea screams revisiting.)

Once Flip Wilson's opening act, Billy Burnette recorded a duet with Bonnie Raitt. A Delaney& Bonnie acolyte, Billy chronicles his brief stint as the duet partner of the Bramletts' daughter, Bekka. The pairing, professionally known and Bekka & Billy, produced an album that, along with Burnette's move to Nashville, should have positioned Billy Burnette as a mainstay of country music's charts.

While Bekka and Billy were critically-acclaimed, disappointing album sales reinforced Burnette's realization that, musically, he is as "country as Manhattan."

In a book detailing lessons learned, like a cat with nine lives, Billy Burnette doesn't sweat the small stuff. He aims for a longevity denied his dad, uncle and Billy's sister, Katina, having already survived hereditary health issues in general, and a quintuple bypass in particular.

While repetitious in spots, and nuanced by typos and an unusually-formatted index, Crazy Like Me is an undeniably good read that delivers as promised.

This book is a love letter to and for Clarence "Leo" Fender, acknowledged by Guitar Player as the father/inventor of the first solid body guitar.

Written by his widow and ghostwriter Randall Bell (the latter a guitarist whose father, a mechanical engineer, oversaw Fender’s "lab" research and development), largely from the perspective of a second wife who met her husband in the autumn of his life, its emphasis is on Leo the man. Leo's creations, the origins of which remain in historical dispute due to the competitive nature of musical inventors such as Les Paul and lesser-known guitar masters), serve as background to the larger story of the late in life romance of an indisputable music icon who was also indisputably a man of quirks and, at times, contradiction.

Consider that while Leo's musical tastes ran toward Roy Clark and other country-music singers (despite the fact that Clark seems to favor Gibson guitars), it was Keith Richards who was on hand for Leo's posthumous induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Richards who contributed a promotional paragraph to this book.

Leo Fender secured his place in musical history well before 2005 when the Fender Stratocaster, the highest priced music memorabilia ever commanded at auction went for $2.7 million; quite a tribute to an unassuming man who, by that time was used to achievements and honors probably bigger than any dreams the Fender family could have imagined following Leo's birth in a California barn back in 1909.

Fender

was still a child when the farm boy lost his right eye.

Disability didn't stop Leo from graduating from Fullerton

Jr. College with a degree in accounting, nor from

marrying fort he first time, but, as a newlywed at a time when men

wanted to serve their country, Leo's blue glass eye disqualified him

from military service.

Always

a a tinkerer, Leo made a career change when the accountant decided

to open his own radio repair shop. Fender

Radio Service would be the first of Leo’s own startups, including the

Fender guitar factories.

Armed with all of the

nearly-singular rights and privileges befitting the young Tennessean entertainment

reporter he once was, Peter enjoyed a backstage pass to the dazzling

panoply of unvarnished, behind-the-scenes conversations and events

before ubiquitous media-training could sanitize many of them.

Why Cooper even got to

co-write with Don Schlitz before leaving the

morning daily (grind) amid administrative changes, layoffs and all the

newspaper business changes that aren't supposed to stifle, nor

otherwise impact, talented, creative self-starters, but often do.

As a reward for the

trust, well-earned industry-wide adulation and respect Peter continues

to enjoy- without objection even from a once-offended Lee Ann Womack- what is now a permanent pass to

the parade has been issued to the Grammy-nominated music producer

in Cooper's current capacity as the Country

Music Hall of Fame and Museum's senior producer, producer and

writer. (Peter moonlights as an

industry-validated songwriter, musician and senior lecturer at Vanderbilt

University’s Blair School of Music.)

While a fan might not have washed his/her hand for days, if afforded the luxury of a handshake from the King of Country Music, Peter Cooper has enjoyed a degree of access that, he reveals, landed him a “prize possession” (that evidently means more to Cooper than any swag bag): Roy Acuff’s last tube of Super Polygrip Dental Adhesive, even as “I won’t tell you the name of (The) New York Times best-selling author who gave it to me.”

While keeping us in

blind-item suspense, Peter entertains readers with appropriately-placed

asides about events that, he suggests, don’t necessarily warrant entire

chapters.

Cooper's

knowledgeable command of subjects like click tracks makes such

subject matter of interest to readers who may not be musicians,

aspiring or otherwise.

While Peter doesn’t